The Characters of Zhi Wei

(and their fondness for them)

by Ara Yun Qiu

Translation by Edel Yang and Julian Dime

Special thanks to Zheyuan Zhang

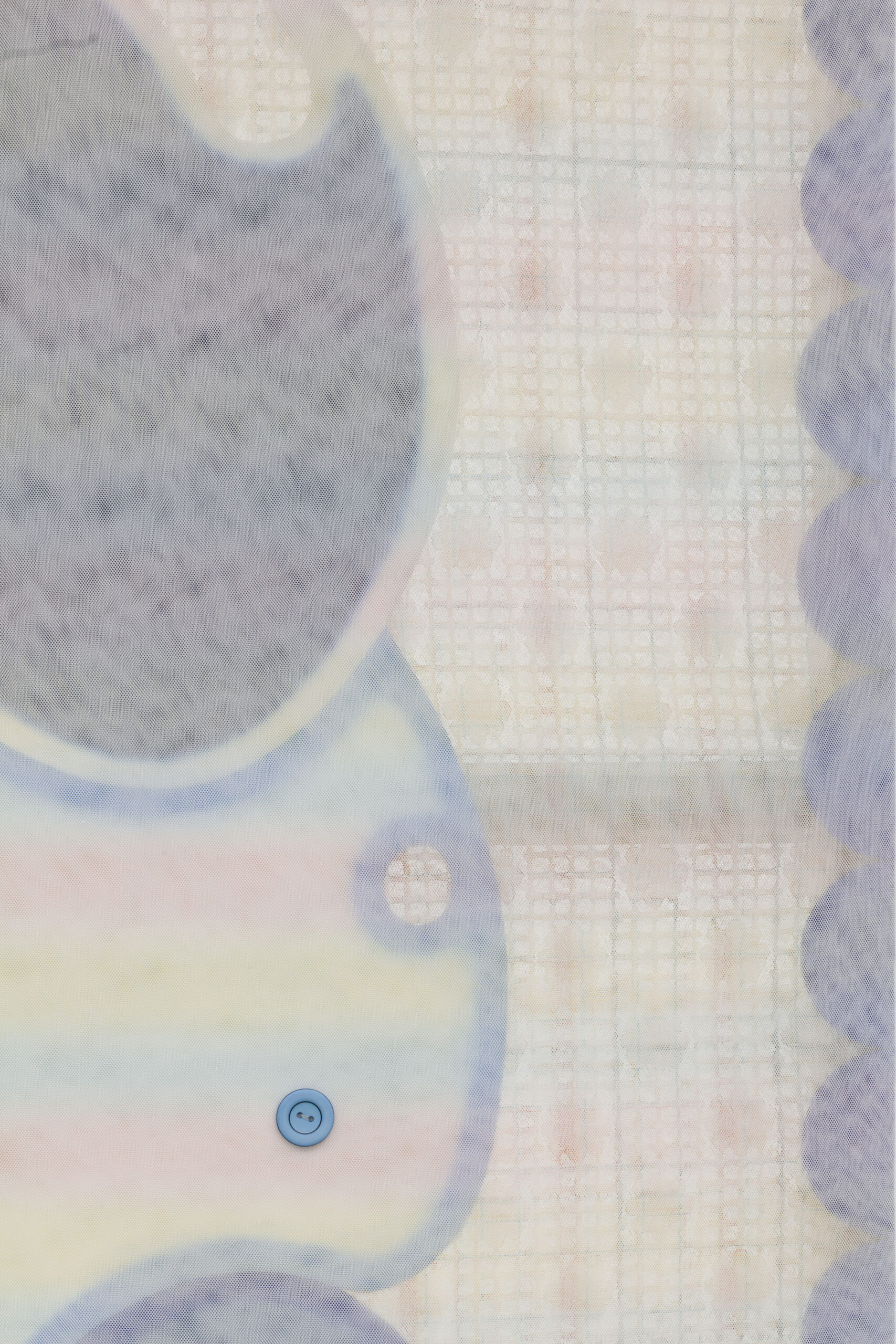

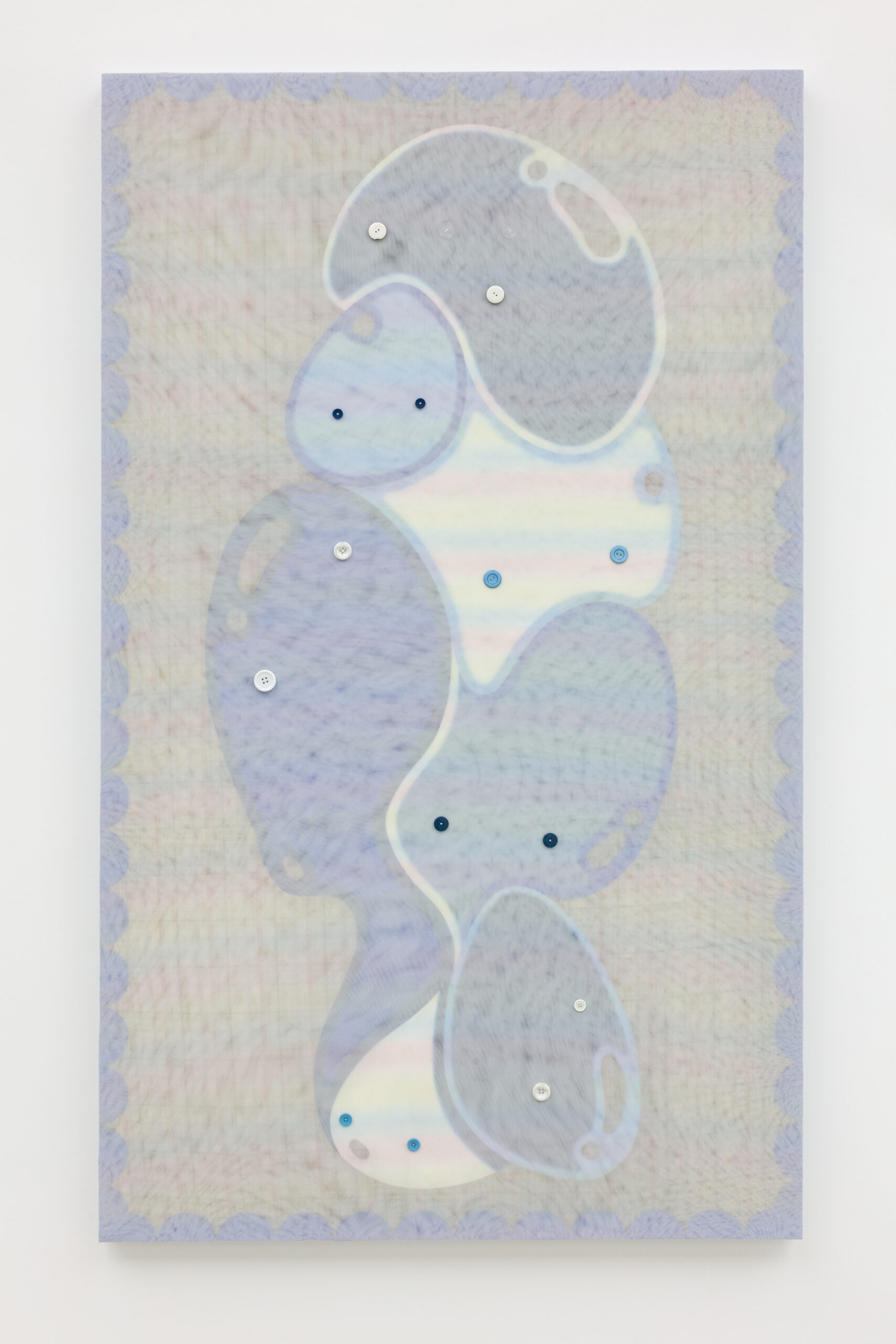

Boy Sensitive, 2020. Acrylic on lace and tulle; buttons and thread,

200 × 120 cm

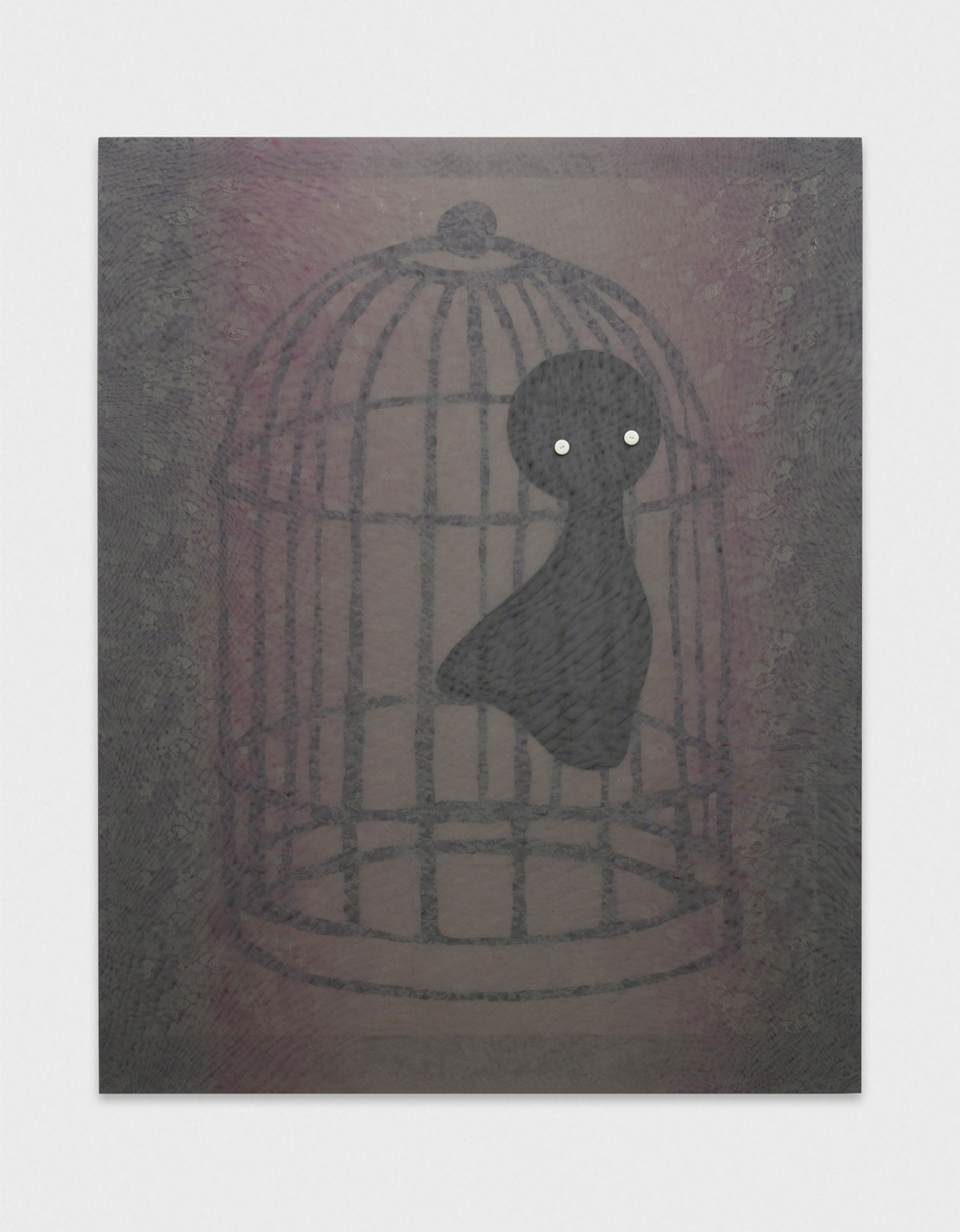

The subject of Zhi Wei’s 2020 work, Boy Sensitive, is a baby-blue-coloured well. The form of the well recalls the wishing well in Disney’s animated movie, Snow White (1937). Segments from such (Disney) films in which the princess sings into the well (or to, more generally, any medium that can reflect her own image) 1 inspired the then Saturday Night Live writer Julio Torres’ 2016 “Wells for Boys” sketch, a commercial parody in which the introverted, “sensitive little boy” Spencer’s favourite toy is a baby-blue ‘Well for Boys’. The sketch has been widely praised as “hilarious, rich, and beautiful” for its compassionate portrayal of boys not fitting the social expectations of masculinity and male gender roles. 2 Zhi Wei depicts the well on layers of lace and tulle. In the work, there is no sign of Spencer. Instead, the artist has sewn the eyes and teardrops of the absent character onto the well, a gesture at once personifying and personal. On the one hand, the well becomes the personification of a hypothetical mass-marketed toy. But more importantly, this relation with the artist transforms the well into a sort of imaginary friend (or companion to the suffering of “sensitive boys”).

Marguerite and a Heart, 2022. Acrylic on Jacquard fabric; tulle, buttons and thread, 200 × 120 cm

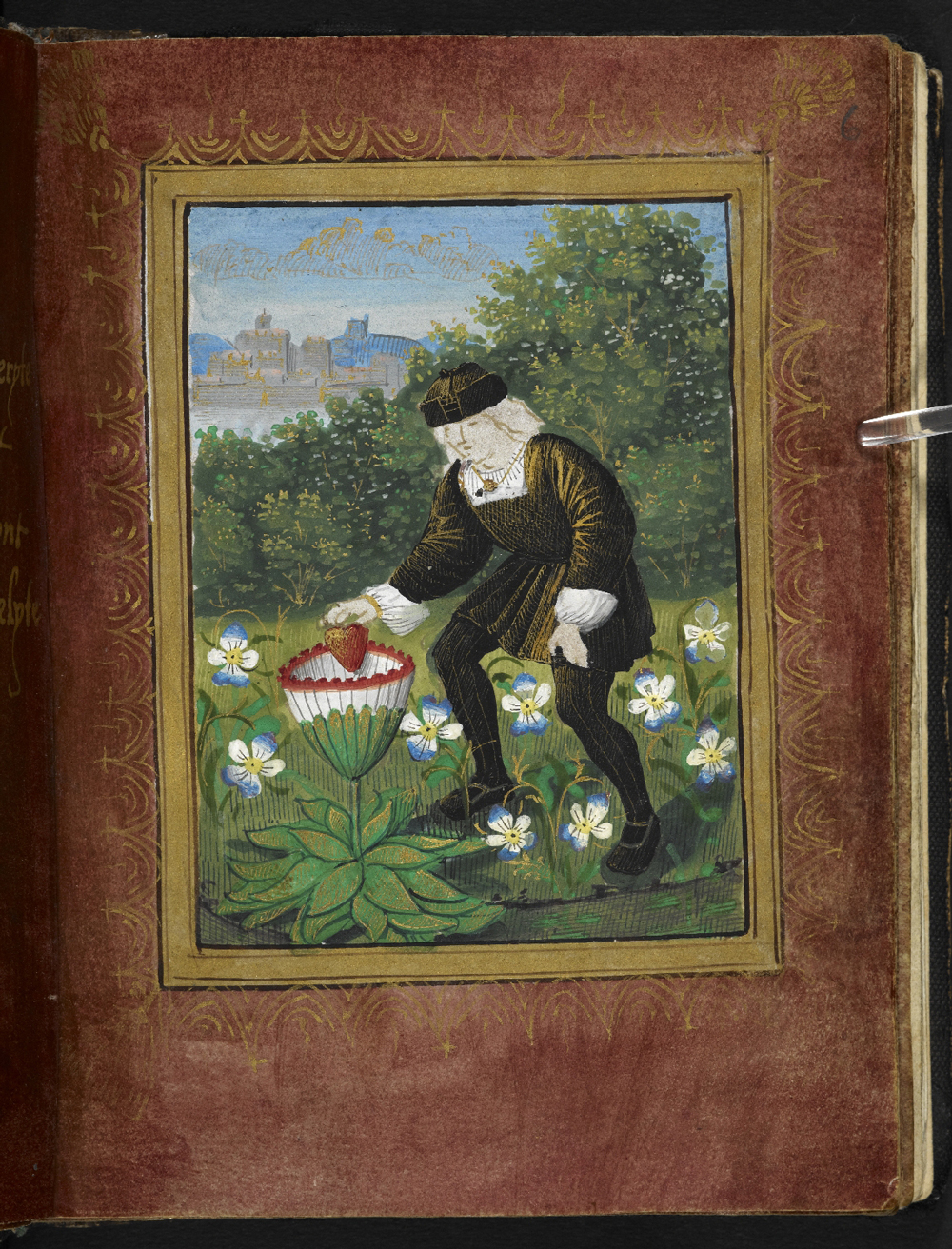

With sharp, jagged teeth around its petals, in the scarlet-toned Marguerite and a Heart (2022), the flower of Marguerite disguises itself as a flytrap as if devouring a red heart hanging down from the top of its crown. The flower is drawn from a beautiful, densely illustrated short poetry anthology, The Little Book of Love (“Le petit livre d’amour”), which the 16th century French antiquary and poet Pierre Salas’s dedicated to his lover Marguerite Bullioud. In one illustration, the poet feeds a red heart to a flowering bud bearing the same name as his lover. Zhi Wei recontextualizes this dedication, focusing on the flower not as the object of love but as an active agent of desire; the flower receives the heart by gently closing her petals. Zhi Wei again avoids the portrayal of the human figure and endows the flower with an emotional character—a pair of red buttons in the calyx resemble eyes, with teardrops falling around its stem and leaves.

Extract from Pierre Salas, Le Petit Livre d’Amour.

Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts, British Library

Zhi Wei’s body of work moves between a wide range of references and inspirations, from American variety shows to the illustrations of rare 16th century French manuscripts, and from late 19th century comic strips of New York newspapers (in The Yellow Gown Revived, 2021-2022) to the early 20th century patterned stained glass window at the Peace Hotel in Shanghai (in Window Puzzle, 2021). Zhi Wei’s inspirations travel freely in time and space, are unusual and unexpected, though they resonate with their personal history and coming of age. Their work becomes an anchor within a deluge of information, from their international upbringing in Beijing, Oxford, Shanghai, from books and movies on their tabletop, or from the internet through which they have been formed.

Zhi Wei’s work, especially their early installations, displays an acute sense of empathy and caring for the characters they describe—the teru teru bōzu (Henry, 2020), the drawstring bag (Untitled #56), and the standing toy bear (Untitled #38) all look like enlarged versions of children’s toys. In enlarging these oftentimes small and intimate objects to the scale of their maker and audience, Zhi Wei imagines a more equal relationship between the objects and humans. Despite their size, the characters still evoke compassion and pity, suggesting at once the vulnerability inherent to childhood and the intensity of ideologies inherited during this formative time. They remind us of Cosima von Bonin’s plush animal sculptures, further reimagining an aesthetic of cuteness in the new millennium.

Henry, 2020. Chinese ink-dyed plaid, buttons, crinoline, inflatable ball, stainless steel cable and thread, approx. 120 × 80 cm

Untitled #38 & Untitled #47, 2018. Acrylic and house paint on MDF,

185 × 116 × 61 cm & 240 × 171 × 114 cm

However, just as the word ‘cute’ was derived from the word ‘acute’ in the 18th century, there is also something gigantesque and uncanny in the “cuteness” of Zhi Wei’s characters beyond their soft plushy exteriors. 3 Suspended in space, the teru teru bōzu Henry looks guileless and playful while also eerily haunting. The same character also appears in The Missing Key Revived (2020/2022), this time as a wandering ghostlike spirit. Zhi Wei’s tendency to reveal the latent uncanniness in everyday mundanity is also evident in Robert Gober’s objects, who Zhi Wei admires; by altering the scale, materials, forms, functions and relationships among ordinary objects, Gober evokes a sense of strangeness and otherness in his staged scenes. As in a phantasmagoric Mulholland Drive-like dreamscape, the wax prosthetic legs jut out from the walls, the sinks and tombstones have eye-like, perforated holes. Like Gober, Zhi Wei is fascinated by this mixture of vulnerability and invasiveness, of banality and spectacle.

Window Puzzle, 2021. Chinese Ink and acrylic on plaid fabric,

200 × 160 cm

Zhi Wei studied contemporary art at a Western academy, where they became familiarized with art histories and theories, though they have often been critical of these traditions. Clement Greenberg’s proposal that modernist art should take medium specificity as its predominant element, which in the case of painting is its flatness/two-dimensionality, was an idea that Zhi Wei positioned their work against. “I don’t really feel with the so-called free movement of the brush,” they noted. “It perhaps suits me better to combine abstraction and figuration, two- and three-dimensionality in the form of Greenbergian ‘non-painting’.”

Combining painting and textiles is typical of Zhi Wei’s approach to making their world of objects and images, disrupting the obsolete but still prevalent dichotomies between high and low, between masculine and feminine, and between fine and craft art in the Western paradigm. It is noteworthy that Zhi Wei’s studio feels like a well-organized couture workshop; it is in many ways the antithesis to the traditional image of an artist’s studio—splattered paint and works strewn around.

While the artist was growing up, their family ran a clothing and fabric business. Drawing from that legacy, Zhi Wei’s works are also composited of multiple layers of fabrics. Heavier fabrics like jacquard and lighter laces are overlaid to form veils and masks, which often function to create a dazzling ‘moire’ interspersed with the fine glitter of thread and buttons. By introducing fabrics of different transparency, Zhi Wei constructs a liminal space in these bas-reliefs, within which they interweave painted fabrics, stretchers, and other materials (papers, buttons and wooden fittings).

Detail, The Missing Key Revived, 2020 / 2022. Acrylic on felt and paper; lace, tulle, vinyl, buttons, thread and ash, 200 × 160 cm

Zhi Wei enjoys working at a steady pace; their technique is labour intensive and done overwhelmingly by hand, involving a minute attention to detail, to the fabric and the frame, the barely visible traces of the brush, the delicate paper cut-outs, and the stitching of the buttons. On the whole, however, the works appear almost digitally perfect. The artist’s technique appears reminiscent, in its immaculate finish, to more industrial practices as in Andy Warhol’s iconic silkscreen prints. But through the layering of material, and the suggestion of dimensionality that perhaps invites the audience into the works, and into their emotional world, this immaculate quality begins to shift toward something else. One has to look carefully in order to distinguish the traces of acrylic paint within the fabrics. The bodies of the characters are in subtle defiance of the aesthetics of the digital age.

Detail, Danny Revived, 2021 / 2022. Acrylic on canvas and felt; lace, interfacing fabric, tulle, buttons, thread and ash, 200 × 120 cm

This ambiguity—the artist’s subjects often teetering somewhere between a twee or cute vulnerability and gigantesque power—is also reflected in the characters that Zhi Wei paints on textiles, which often begin resembling more clearly human figures at the artist’s scale, a sort of standard self-image. They then cover up this ‘standard self’ with layers of soft varied lines and shapes, transforming it into something grotesque, an unidentifiable but adorable image of the “other”. Jesse, John, Alex and Timothy all appear as ghostlike “quasi-subjects,” 4 that Zhi Wei refers to as their intimate friends: “In the studio, I am both making friends as much as I am making friends with them.”

Zhi Wei has lived with created or manufactured objects since their childhood. A sort of Pygmalion complex emerges in Jax Duplicated No. 1 and Jax Duplicated No. 2, a diptych featuring the “Neo-Victorian robot” Jax, one of the machines from Ted Chiang’s short story, The Lifecycle of Software Objects. The story imagines a metaverse in which humans raise virtual pets called digients. Ana, the story’s protagonist, in raising Jax observes that life as an “experience is algorithmically incompressible.” 5 Like Ana, Zhi Wei cares for her characters as friends or children, such that the works become relational gestures. It is a work of giving life to something or to someone, a work of love for which there are no shortcuts.

Jax Duplicated No.1 & No.2, 2022. Acrylic on Jacquard fabric; tulle, buttons and thread, 200 × 120 cm each

In 2022, Zhi Wei’s Beijing studio was partially destroyed by a fire whose smoke blackened Danny and Jimmy (though, fortunately, the surface textile accidentally protected the painted parts). After replacing the textile, Zhi Wei renamed the two works Danny Revived and Jimmy Revived and added ‘ash’ to the list of materials. Like an attentive friend, they tended to the characters, while recording the disasters suffered by their companions and their eventual rebirth. The vitality that the artist gives to the images also evokes the unique feeling that the viewer has when looking at the Rabbit-Duck illusion or the Necker Cube: the drawings are more than just lines, shapes or colours on a flat surface, but are also crowned as icons, fetishes, and magic mirrors. Referencing toys that require necessarily some sort of human animation, they are objects that, though invested originally by the artist, come to have a lives of their own, able to speak to us and look at us. 6

Zhi Wei’s work invites the viewer to explore all its tensions, contradictions, and ambiguities; it is a practice that develops myriad readings, that seeks often to marry opposing forces. From different vantages, the works assume different characters, and the characters themselves oscillate between a kind of benign cuteness and a monstrous gigantism. Zhi Wei plays with scale and technique, overlaying materials that occult alternative aspects of their characters. We are asked to befriend these characters, to engage them as the artist might, with honesty and without being blind to tears.

Danny Revived, 2021 / 2022. Acrylic on canvas and felt; lace, interfacing fabric, tulle, buttons, thread and ash, 200 × 120 cm

The legacy of childhood permeates Zhi Wei’s work; the sensitive little boy is circled over again, his overactive imagination has perhaps conjured the gigantesque reliquaries of his angst, his toys grown to a scale at which they have become nightmarish. The artist’s weaves through their work the symbology of this formative period—one tainted by the at once banal and intensely real trauma of learning, growing up, assimilating from the possibility of early childhood into convention, more normative social frameworks. It is, however, also a period of play, and the imagination, the work might lead us to believe, can conjure up something that escapes convention, that skirts what might otherwise be possible. Zhi Wei reworks the fabrics of their family’s business, the familiar plaid patterns that coloured their early life—which is a type of pattern that is also gendered, normative—into their characters. As such, they become new models for living, substitutes for the artist that can themselves be reparented and go on to live their own lives. Through play, the imagined becomes actualized, the works become characters, and the characters become the life work of the artist, who reveals themselves otherwise, refigures themselves always through and in relation to them.