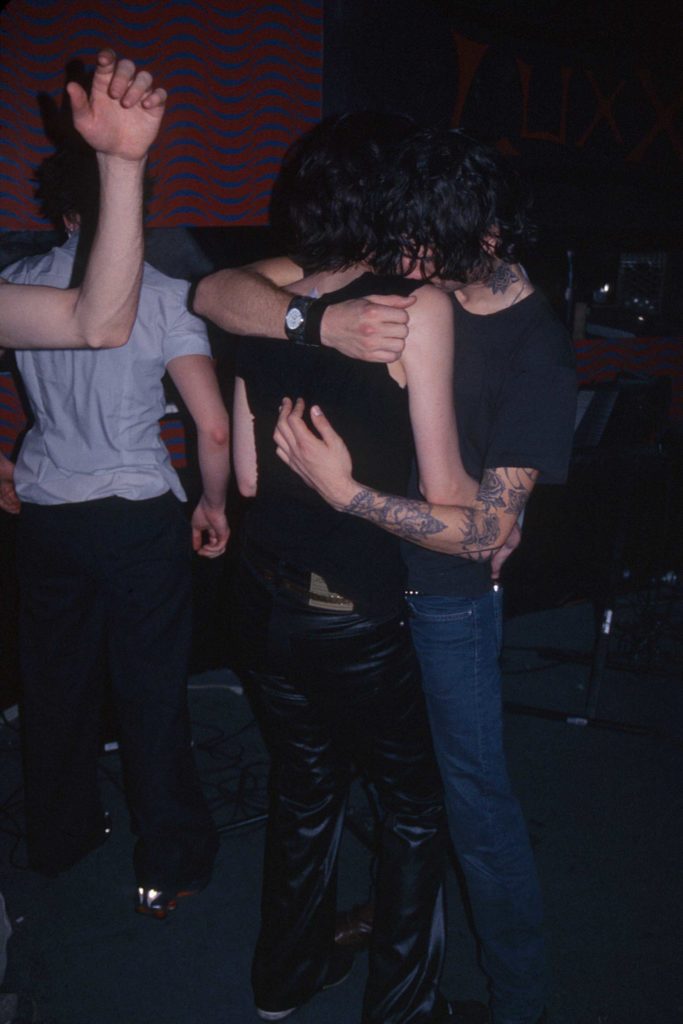

“La Boom” party at Warsaw, 2002

(all photos are by Craig Garrett unless otherwise noted)

A conversation between

Daniele Balice and Craig Garrett

DANIELE: Craig! I met you right after I moved to New York, a few months before 9/11. I was too young and naive to fully understand the crazy shift that happened right after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, but you were a guide of sorts as I figured out the nightlife and the emerging art scene. Could you summarize the way you were living then, and how those scenes changed?

CRAIG: I moved to New York in the summer of 2000, not long before you did. During those first few months it seemed like everyone I met would say, “You just moved here? Man, this city used to be so exciting. You really missed out.” Which I soon realized is a perennial truth about New York.

You and I moved here from two very different places — Milan and San Francisco — but in the art world we were both on the bottom rung of the ladder. I ended up spending more time in the music scene, where there was actually a lot happening, but none of it had to do with art. The exception, of course, was Fischerspooner. If we’re going to talk about electroclash, we should acknowledge them. They were artists first and musicians second, but they anticipated the attitude and aesthetic of electroclash by a couple years.

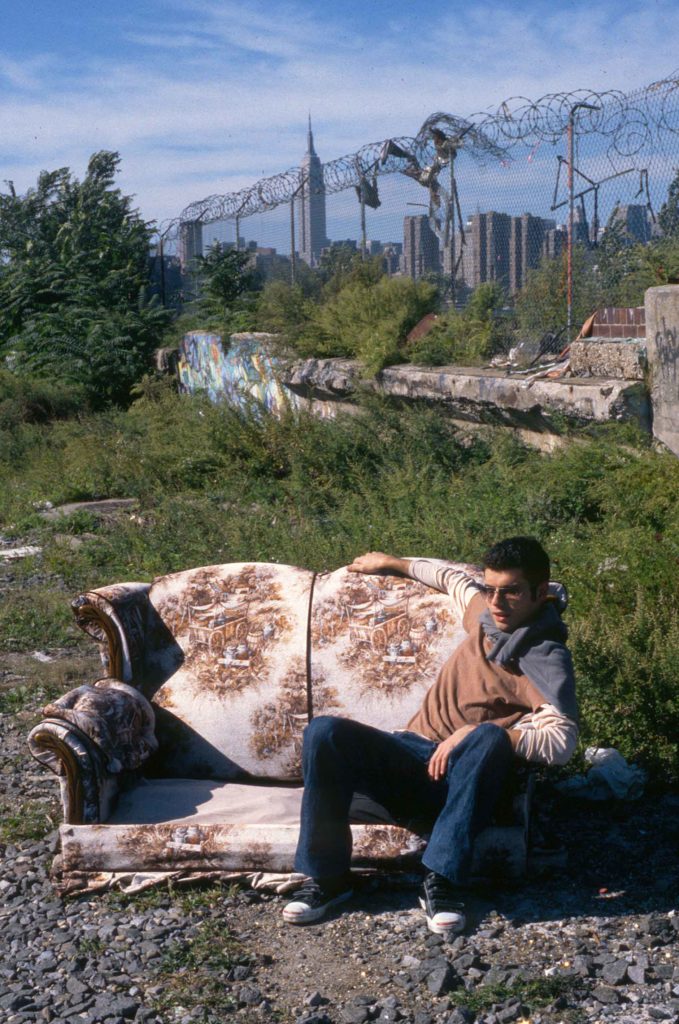

Craig Garrett, 2002 (photo by Alex Antitch)

Daniele Balice, 2001

DANIELE: Right! Actually, the first time I went to New York was to interview the lead singer of Fischerspooner, Casey Spooner, for a European magazine. Maybe it was 1999, and we met at the Passerby, Gavin Brown’s bar. As you know, I ended up renting a room from another member of Fischerspooner when I moved to NY. I have always been fascinated by this convergence of the art world with the music scene. However, to go back to 9/11, things shifted drastically. We both started going to Luxx, this club in Williamsburg. Remember that?

CRAIG: Yeah, of course. Berliniamsburg, Larry Tee’s weekly party at Luxx, started a month after 9/11. My first visit was probably the second or third week, and the energy was totally different from any nightclub I’d ever been to. I was so excited, I think I called you about it the next morning.

That moment in New York was really unique. People might not remember now, but the city’s reaction to the attacks was very different from the rest of the country’s. Even though there was mourning and American flags everywhere, the disruption to the city’s normal rhythm also opened up a space for reimagining life. People reacted to that disruption in a lot of different ways. My friend was a bartender at the Cock, and he said that 9/11 was the busiest night they’d ever seen, just nonstop drinking and fucking.

“Berliniamsburg” party at Luxx, 2002

DANIELE: What kind of music was playing in that moment? Who were the DJs and bands?

CRAIG: At the beginning we were listening to music made in Europe and Detroit, largely from offshoots of techno scenes, which is ironic because the electroclash crowd wasn’t really familiar with dance music. Most of us were arty kids from the American suburbs brought up on rock, goth, emo, punk, and new wave. A lot of the DJs in the scene didn’t know how to mix two songs together—not that the dancefloor even cared! We were finally in a dance club, and we just wanted to go wild.

The attitude in the beginning was sleazy and flirty, but also nonpredatory, maybe because the crowd was about 50/50 gay and straight. Something about that chemistry was perfect. But by the spring of 2002 something had changed. The New York Times started writing about electroclash, and the crowd turned more homogeneous. Berliniamsburg basically became a club for gay men, which was where Larry Tee and Spencer Product had come from anyway. A lot of us who’d been there at the beginning left to find our fun elsewhere. We ended up starting our own nights at bars like the Hole, where you could do whatever you wanted without worrying about tourists or the New York Times.

Miss Kittin & The Hacker at the Frying Pan, 2000

DJ Lez Celeb at Opening Ceremony, 2002

DANIELE: I clearly remember that time: people were living like every night was their last. Simultaneously, though, I recall how hipsters started dressing like rednecks. All the restaurants started hanging taxidermy animal heads on the walls and serving typical American food. Somehow a conservative, white aesthetic took over in a very disturbing way.

CRAIG: Yeah, it took a weird turn. Electroclash was a hybrid style. It borrowed from a bunch of different subcultures, like new wave (the skinny ties and sleeveless T-shirts), heavy metal (studded leather belts), hip hop (Nike Dunks), plus some Puerto Rican flair from the local thrift store. The goal was to stand out from the crowd. And instead of buying your look from an expensive store, you created it yourself. (If we had more time we could do a whole conversation about DIY electroclash haircuts.)

Meanwhile, there were these other hipsters ironically appropriating from the rural white working class (who they called, unironically, white trash): the moustache, the hunting camouflage, Pabst Blue Ribbon beer, and of course the trucker hat. The guys with this style (it was mostly guys) were the roommates of the electroclash kids, or they were the art handlers at the same museums where the electroclash kids worked in the bookstore. At the time, most of us didn’t consider the implications of these guys dressing like rednecks. It seemed like free semiotic play, all in quotation marks. But soon the fashion industry needed a new trend, and they latched onto this Americana thing, probably because they thought it suited the post-9/11, pro-USA mood. All they had to do was tidy it up and make it expensive. So what started out as an ironic moustache in 2001 suddenly became the focus of a multimillion-dollar facial-hair grooming industry.

In retrospect it’s clear that a lot of those Pabst guys had anxieties about class and masculinity, probably about race, too. I don’t want to give Gavin McInnes too much credit, but he latched on to that aesthetic early, after moving to New York from Montreal, in 2001. Soon after that, his magazine, Vice, started fetishizing white rural America. Every issue had at least one photo of a bleeding deer hanging out the back of a hunter’s pickup truck.

Since then we’ve seen how important irony was to the rise of the alt-right. It was a risk-free way for people to try on an extreme reactionary position. If you criticized their racist/sexist/homophobic statements, they would just laugh and say they were trolling you. It only took Gavin a decade to go from New York hipster to professional white-nationalist with his own paramilitary group. And guess what they wear instead of brown shirts? Red trucker hats.

DANIELE: It’s interesting that you mention this turn. I also remember New York had an inspiring and very visible transgender community, but it seemed to dissipate under the pressure of an increasingly sterile, heteronormative city. On a positive note, I feel like now, even under the current political conditions, there is a strong, diverse, and proud community forming. Do you think the same energy we experienced back then will return?

CRAIG: One thing I learned from all those people telling me I moved to New York too late was that there’s always something exciting happening here, just not in the places where everyone’s looking. That has been true for decades. But it’s also true that this city keeps getting harder for creative young people to live in—unless they’re lucky enough to have mommy and daddy paying their rent. City and state policies that favor the rich, as well as the wealth-hoarding that’s happening across the United States, are responsible for turning New York into a dull monoculture. And the pandemic is about to supercharge this problem. You’re right, though. There are still amazing communities here, and they will help each other struggle through. I guess we’ll see what the city looks like when we reach the other side.

During the early 2000s Craig Garrett lived in Brooklyn while writing about art, working at a library, editing a music zine, throwing parties, and playing records under the name DJ Boyfriend. Today he lives in Brooklyn again, where he raises a one year old, makes art books, and still occasionally deejays. Since 2012 he has worked as the editorial director for Matthew Marks Gallery. Before that he spent eight years in London as the commissioning editor for contemporary art at Phaidon. Here’s a mix he made in 2002 to promote La Boom, a weekly party he organized with Ihu Anyanwu in Greenpoint: DJ Boyfriend “Glass Curtain” on SoundCloud